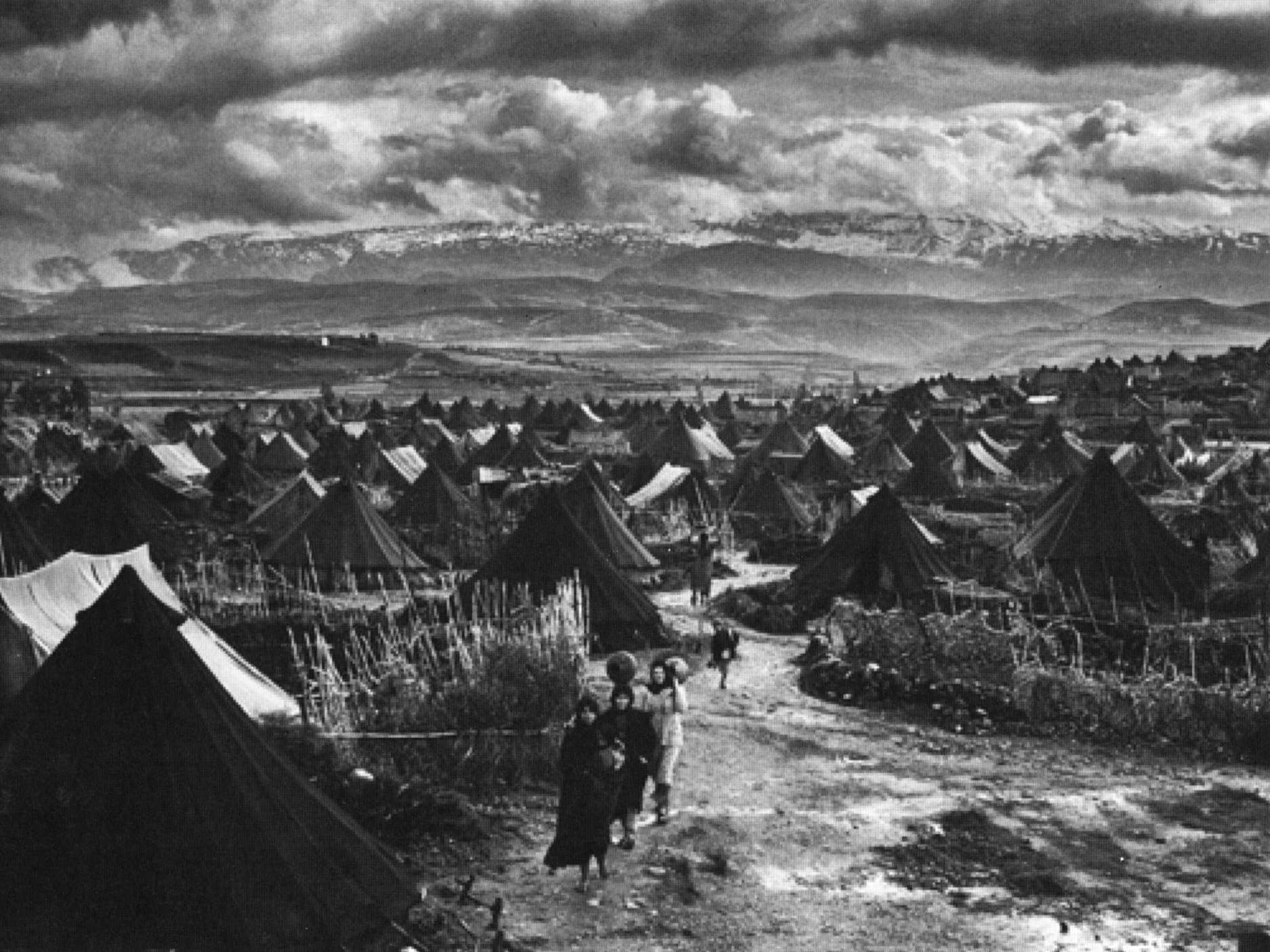

Palestinians in Lebanon

Between the end of 1947 and 1949, some 750,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled from their homes by Jewish military forces and forced to leave Palestine(1). The result of this, which some historians consider to be a process of ethnic cleansing(2), was that the land in Jewish possession increased from less than 6%(3) to 78%(4) of the entire Palestinian territory and eventually made up the newly formed state of Israel: this event is known in the Arab world as al-Nakba, “the catastrophe”.

These three quarters of a million Palestinian refugees took shelter mainly in neighbouring countries: in Jordan, Syria, Lebanon and other Arab states(5), meeting perhaps different fates, but united in the impossibility of returning to their homeland. Of this first migratory wave, about 100,000 Palestinians took refuge in Lebanon(6). This forced exodus underwent a second wave in 1967, following the “six-day war” (through which Israel gained control, among other areas, of the Gaza strip and the West Bank, in fact appropriating all the territory destined to Palestine foreseen in the 1947 United Nations resolution(7)).

Each host country has managed the Palestinian refugee issue individually: while Jordan has perhaps made the greatest efforts to integrate Palestinians into the national fabric, and in Syria they enjoy almost full civil rights, in Lebanon, substantial restrictions are still in place(9). The vast majority of Palestinians living there have not yet obtained Lebanese citizenship, despite the fact that the vast majority of them were born in Lebanon and their families have lived there for generations. In fact, after more than 75 years of living as refugees, the fourth generation of the 1948 refugees now survives in the Lebanese refugee camps, while those who lived in historic Palestine at the time, which had just come out of the British Mandate, are now elderly people on the verge of disappearing into silence: almost half of the Palestinian refugee population in Lebanon is under 25 years old(10). To date, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) has almost 490,000 registered refugees in Lebanon(11), 80% of whom live below the local poverty threshold(12).

But where do Palestinians live in Lebanon? At first, between 1948 and the beginning of the next decade, they were mainly settled in rented houses, or hosted by relatives or acquaintances; a minority stayed in tents or were housed in mosques, monasteries or similar places(13). Then, in the 1950s, they were progressively concentrated in a series of refugee camps and informal settlements(14), under the aegis of the United Nations and the newly founded UNRWA. Today, there are 12 refugee camps where UNRWA operates(15), but there are other informal settlements in the country, which the agency does not deal with.

“None of the camps have any formal infrastructure. Some camps were partially destroyed during the [Lebanese] civil war and the Israeli invasion [of 1982] and were never rebuilt. There is a lot of poverty and the unemployment rate is very high. The area of land allocated to the camps has remained the same since 1948. Thus in the more populated camps, the refugees could only expand upwards. Construction is not controlled and buildings do not conform to international safety standards.”(16)

This situation means that in some camps the streets have become tunnels no wider than one’s shoulders; those who live on the ground floor of these streets can never catch the sunlight. In some camps there is no drinking water: the running water is drawn directly from the sea and it is salty (as in the Shatila and Mar Elias camps in Beirut). To this one must add an inadequate sewage system, as well as difficulties and discontinuities in the electricity supply. The Lebanese state does not take care of the camps: it merely provides a “security” service. The camps have a well-defined perimeter with entrances often controlled by the Lebanese army. In general, camp residents are free to enter and leave, but there may be more or less strict controls (as in the Ain el-Hilweh camp, considered probably the most “difficult”, where the army patrols every exit, and which is closed to non-residents). In the camps UNRWA provides education, social and health services, food support(17).

But the consequences of not being able to obtain full citizenship (except under special conditions or rare historical and political circumstances involving a limited number of individuals) are extremely serious for this population: the Lebanese legislation denies “foreigners” a long series of rights; it should be kept in mind that the most numerous “non-Lebanese” community residing on the surface of the State is precisely the Palestinian one (representing almost 9% of the total population(18)). Palestinians are denied access to the Lebanese health service, they are denied access to public education, they do not have the right to vote. Access to the world of labour for them is severely restricted: for decades, they could not legally exercise any of some 70 different professions; in recent years, the situation has begun to change, but probably more in the form than in the substance. For example, in 2021, the Ministry of Labour opened the possibility for “Palestinians born in Lebanese territories and officially registered with the Ministry of Interior” to exercise professions regulated by professional orders(19); nevertheless, many of these orders do not allow any “non-Lebanese” to register by internal regulations(20). Not to mention the difficulty in dealing with the bureaucracy of obtaining permits and registrations: as of 2019, for example, the Ministry of Labour has decreed that Palestinians must still receive a work permit in order to exercise any profession(21). This complicated and unclear legal situation actually opens the door to illegal work and the exploitation that goes with it, or limits employment opportunities to unskilled professions, such as labourers, merchants, and farm workers.

An article in 2006 stated that “the 5 main sources of income of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon are: employment with UNRWA; remittances from relatives working abroad; employment in Palestinian associations or organizations; employment in agriculture and Lebanese companies; employment in shops and enterprises within the refugee camps.”(23) This could still be applied today, notwithstanding the small steps forward made at a legislative level. Moreover, again on a legislative basis, Palestinians are not allowed to own or inherit property(24); any lease or sale contract must therefore be signed through a proxy; upon the death of the Palestinian owner, the property becomes government property. These restrictions on working and living, combined with Lebanon’s own economic crisis, prevent the Palestinian population from accruing any form of wealth, making their civic situation increasingly unstable and actually dooming them to live within the refugee camps, with all the complications that this entails.

On top of this is the limited freedom of movement: since Palestinians are stateless, they do not have an official identity document; only those who are registered with UNRWA obtain a residence document and a document valid for travel (valid for 5 years, renewable). In any case, in order to move outside the borders of the Lebanese state, one needs to obtain a visa, the approval of which is never to be taken for granted(25).

“[The Lebanese] consider us foreigners, but even foreigners have more rights than we do. The foreigner has the right to own, to buy… the Palestinian has no rights in Lebanon. This discrimination, they say, is because we are going back to Palestine. Right, but I am a human being, I want to live”.

Palestinian refugee from Shatila camp(22)

“You’re asking about the reasons for unemployment, while we as Palestinians are deprived of our basic rights. We’re not allowed to work, and when we work, we can’t take any days off or receive service indemnity, and we can’t have any property. We’re deprived of all of our rights”.

Palestinian plumber, 52 years old, Mieh Mieh camp(39)

A possible way out of this situation is for women to marry a Lebanese man: in this case, the Palestinian bride may obtain Lebanese nationality one year after the marriage registration, but only in case of a favourable judicial decision(27).

Ultimately, the most basic rights are denied to Palestinians living in Lebanon: despite the reception accorded to them in the very early stages of their exodus, to this day the situation is not only unsustainable and cause of great marginalisation, but also has a profound impact on the health, wellbeing and life expectancy of the Palestinian population. A study conducted in 2012 among households known to UNRWA found that more than 30 per cent of those surveyed suffer from a chronic illness and 24 per cent from an acute illness in the previous six months; that more than half of the women suffer from psychological problems; that more than 40 per cent of the homes have water infiltration, which negatively affects the prevalence of chronic illnesses(28). Although these figures do not differ substantially from the overall global prevalence of chronic and acute illnesses, the adverse living conditions make their outcomes very serious and the overall impact on the daily lives of sufferers very profound.

Conditions for children are very difficult: overpopulation and exposure to violence are two major risk factors(29). One study found that school attendance is reduced by the “high prevalence of loneliness, worry, and suicidal ideation”(30). This whole picture has repercussions on mental health, which in a camp such as Shatila is neglected in primary care(31), and on psychosocial well-being, with a large part of the population reporting emotional, behavioural, psychosomatic problems (tension, anxiety, sadness, exhaustion, hyperactivity, learning difficulties…)(32). This situation has been further aggravated by the onset of the Syrian crisis, with further exposure to problematic and potentially traumatic events(33).

What existential perspectives can an individual who is born in this environment, from the womb of a mother who has known only this, for generations, as her mother and her mother’s mother before her? Where the memory of living a life free to express and develop, to dream and become, fades out with every passing day? The Nakba of 1948 is not an isolated, self-contained episode: it was the beginning of a process that to this day knows no conclusion. The Israeli-Palestinian question has never been solved as, generalising, neither Israel has ever granted a return to Palestinian refugees, nor have Palestinians ever abandoned the ideal of returning to their homeland, to their homes. This visceral attachment to their violated past, the feeling of injustice they suffered, created a precise and inflexible identity of an entire population, which has kept it alive for more than 75 years through a troubled existence, marginalised, abused and forgotten by most. It went through the Lebanese civil war, the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, suffered betrayals, massacres (see the terrible case of Sabra and Shatila(34)). It is therefore no surprise that a 2020 qualitative study addressed to Palestinians in Lebanon found “unsafety as a pervasive psychological experience: everyday fears of survival and harassment can be as stressful as fears of armed clashes or crime for Palestinian refugees”, and that “Palestinian refugees are pessimistic about the future and many see resettlement to another country as the only solution.”(35)

Shatila camp mental health

A sample of 254 primary health care clinic patients in Shatila was screened for mental illness between 2012 and 2013. Mental illness prevalence was 51.6% in total: 34.8% serious mental illness [SMI] alone, 5.1% PTSD alone, 11.4% comorbid SMI/PTSD(36). For a quick comparison, consider that WHO has estimated global mental health prevalence stating that “in 2019, 1 in every 8 people [12,5%] […] were living with a mental disorder”(41).

“You’re asking about safety, but where is it? What is safety? How do you want me to be safe and sound while I’m unable to undergo medical treatment or even see a doctor?”(37)

“Of course I don’t feel safe. I’ve lost the feeling of safety. I’m afraid of everything, due to everything that has happened to us. How will I feel safe, after my country went through all of this destruction, catastrophes, leaving us with fear? There is no safety at all…”(38)

Of course, leaving Lebanon for another country may look like a way out, but given the restrictions on travel and global migration policies, it is often not viable except in clandestinity. One possibility, for young people, is to be very good at school and receive a scholarship (provided by one of the various humanitarian organisations working in this direction) allowing them to study abroad: they will at least have a choice. Afterwards, some of them return to Lebanon to support their families from nearby, perhaps no longer living in the camp of origin, but close by, or still maintaining a “connection”(40). But there are also those who have no intention of leaving: they think that, after 75 years of “temporary stay” in this situation, the living conditions for them and their children will not change unless they continue to fight for their rights, with all the uncertainty about the results that these 75 years have shown. And anyway, their lives as exiles, their family and friendships, reside in these non-places.

This is the context in which Music & Resilience works. Over the years, many people have succeeded one another in the project, both in the Italian team and among the Palestinian beneficiaries and collaborators, and bonds of friendship, respect and sharing, both human and professional, have been forged between many of them, which are not limited to the context of the project itself. These are perhaps small safe spaces where we can meet and learn together the fragile art of existence.

January 2024

Notes

- Slater, J. (2020, p. 81). Mythologies Without End. The US, Israel, and the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1917-2020. Oxford University Press. ^

- Pappe, I. (2006). The ethnic cleansing of Palestine. Oneworld; cfr. Slater, cit., p. 84. ^

- Pappe, cit., p. 18. ^

- Khalidi, R. (2020, p. 60). The Hundred Years War on Palestine A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917–2017. Metropolitan Books. ^

- Morris, B. (2006, p. 52). Righteous Victims. A History of the Zionist-Arab Conflict, 1881-2001. Vintage Books. ^

- Amnesty International (2007, p. 12). Exiled and suffering: Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/mde18/010/2007/en/ (retrieved January 7, 2024). ^

- Slater, cit., pp. 137-138. ^

- Fisk, R. (2001, §2). Pity the nation: Lebanon at war. Oxford University Press. ^

- Bowker, R. (2003, pp. 72-76). Palestinian Refugees Mythology, Identity, and the Search for Peace. Lynne Rienner. ^

- UNRWA (2018). Protection brief. Palestine refugees living in Lebanon. https://www.unrwa.org/sites/default/files/unrwa_lebanon_protection_context_brief_june_2018.pdf (retrieved January 7, 2024). ^

- UNRWA (n. d.). Where we work. Lebanon. Retrieved January 7, 2024 from https://www.unrwa.org/where-we-work/lebanon; the actual figure is difficult to compute, as registration is voluntary and it is not easy to take births, deaths and emigrations into account; a 2017 government census counted approximately 174,000 total Palestinian refugees (https://www.pcbs.gov.ps/portals/_pcbs/PressRelease/Press_En_Leb-21-12-2017-results-en-2.pdf retrieved January 7, 2024). ^

- UNRWA, cit. ^

- El Ali, M. (2010, p. 23). Overview of Palestinian Forced Displacement in and from Lebanon 1948-1990. Al Majdal (44). BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights. https://www.badil.org/phocadownload/Badil_docs/publications/al-majdal-44.pdf (retrieved January 7, 2024). ^

- Ibid. ^

- UNRWA, cit. ^

- Shafie, S. (2006, p. 5). Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon. ^

- Ibid.; UNRWA, cit. ^

- Excluding the refugee population from Syria during the Syrian civil war (approximately 1.5 million people); of these refugees, a large proportion were Palestinians who had fled to Syria. ^

- Mahfouz, A., Sewell, A. (2021, 8 December). Labor Minister decrees Palestinians can work in professions requiring syndicate membership. L’Orient Today. https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1284128/labor-minister-decrees-palestinians-can-work-in-professions-requiring-syndicate-membership.html (retrieved January 7, 2024). ^

- Saghieh & Nammour (2015). Labor rights of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. Access to liberal professions. International Labour Organisation. ^

- Makhlouf, R. (2022, 13 January). Palestinian Work Permits in Lebanon: an overview of the decree and its political backlash. Kayani. https://www.kayaniforpalestinianfemalesproject.com/news/n93hze7stlnnlrx74u4snvjcs3czr4 (consultato il 7/1/2024). ^

- Salih, R. (2020, p. 152). I rifugiati e la politica catartica: dai diritti umani al diritto di essere umani. Il Ponte, Gennaio-Febbraio 2020. ^

- Shafie, cit., p. 12. ^

- El-Natour, S. (2003). The Palestinians in Lebanon. New Restrictions on Property Ownership. In Holy Land Studies, vol. 2(1). Edinburgh University Press. ^

- I have personal experience of friends being denied a visa for a leisure visit to Italy, without being provided any explanation. ^

- Barghouti, M. (2004, p. 134). I saw Ramallah. Bloomsbury. ^

- Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion (2021, p. 7). Country submission: Lebanon. Universal Periodic Review session 37. https://files.institutesi.org/UPR37_Lebanon.pdf (retrieved January 7, 2024). ^

- Habib, R., Seyfert, K., Hojeij, S. (2012). Health and living conditions of Palestinian refugees residing in camps and gatherings in Lebanon: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet, vol. 380 (1). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60189-0. ^

- Jamaluddine, Z., Irani, A., Salti, N., Abdulrahim, S., Chaaban, J., El-Asmar, K., & Ghattas, H. (2021). Child deprivation among Palestinian refugees in Lebanon and Palestinian refugees from Syria living in Lebanon: a cross-sectional analysis of co-occurrence of deprivation indicators. Lancet, vol. 398, S32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01518-X. PMID: 34227965. ^

- Nathani, K., Lee, WC., Taha, S. et al. (2023). The Association Between Mental Well-Being and School Attendance Among Palestinian Adolescent Refugees in UNRWA Schools. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma vol. 16, 339–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-022-00460-7. ^

- Segal, S.P., Khoury, V.C., Salah, R., Ghannam, J. (2020). Unattended Mental Health Needs in Primary Care: Lebanon’s Shatila Palestinian Refugee Camp. Clinical Medicine Insights: Psychiatry, 11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1179557320962523 ^

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH, UNRWA (2014). Mental Health and Psychosocial Wellbeing Among Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon. https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/45359 (retrieved January 8, 2024). ^

- Medical Aid for Palestinians (MAP, 2018). Health in exile. Barriers to the health and dignity of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. https://www.map.org.uk/downloads/health-in-exile–barriers-to-the-health-and-dignity-of-palestinian-refugees-in-lebanon.pdf (retrieved January 7, 2024). ^

- See for example Fisk, cit., §11. ^

- United Nations Development Fund (UNDP, 2020, p. 6). Nothing and everything to lose. Results from a qualitative Whatsapp survey of Palestinian camps and gatherings in Lebanon. https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/lb/UNDP-WhatsApp-Survey-Report_Final.pdf (retrieved January 8, 2024). ^

- Segal, S.P., Khoury, V.C., Salah, R., Ghannam, J. (2018). Contributors to Screening Positive for Mental Illness in Lebanon’s Shatila Palestinian Refugee Camp. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 206(1), 46-51. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000751. PMID: 28976407. ^

- UNDP, cit., p. 16. ^

- Ibid., p. 48. ^

- Ibid., p. 37. ^

- This is not exclusive to the Palestinian refugee community in Lebanon; see Achilli, L. (2020, p. 183). Alla ricerca della dignità. Economia politica e nazionalismo nel campo profughi di Al-Wihdat, Amman. Il Ponte, Gennaio-Febbraio 2020. ^

- World Health Organization (WHO, 2022, 2 June). Mental disorders. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders (retrieved May 17, 2024). ^